Look, there, on the wall: the most exquisite Victorian wallpaper pattern. On a blush of delicate pink, the color of a clamshell’s interior, eight circles burst from a round center, each with a triangular marking inside. Come closer. Further enter the welcoming room, furnished with warm wooden antique cabinetry and lit with chandeliers, so you can better admire the wallpaper — except it isn’t wallpaper. It’s an arrangement of cicadas, hundreds of them, once alive and now carefully preserved and pinned to the walls in what artist Jennifer Angus calls the “poetry of pattern.”

“I always describe it as a compulsion and then a repulsion,” says Angus, a professor in the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Textile and Fashion Design program whose insect art has been shown around the world (including an eight-month run at The Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. — part of the museum’s Wonder show that drew half a million people). In this particular exhibition at the Staten Island Museum, even the pink of the walls comes from bugs — in the form of lac, a coloring produced by scale insects (it’s the same natural dye used as shellac varnish). In the face of all this unexpected beauty, Angus hopes you leave her exhibitions with a newfound appreciation for the often-maligned insects that make our lives possible.

“As I came to learn more about insects, I [realized] how important they are to our very existence on this planet,” Angus says. “So I played with that tension, that fear, for a long time. But more recently, I’m interested in using my exhibitions as a platform to have a discussion about many things, but specifically insects — how they are, like all of us, threatened by climate change, loss of habitat and, of course with insects, pesticides.”

Angus only creates site-specific installations, essentially pop-up exhibits, at the museums, galleries and venues that invite her in. She reuses all the insects from exhibit to exhibit. The vivid colors are their own — she doesn’t paint them — and if something is broken beyond repair, she saves the parts to make hybrid creatures. Apart from the patterned “wallpaper,” you’ll find these insects posed in whimsical domestic displays — reading tiny little fire-singed books to represent burned or banned books (as well as climate change), or crawling on the taxidermied animals that are gathered around a dinner table at the center of the room. Her installations aren’t just beautiful, they always contain layered messages intended to make you think — to act. Time and again, Angus finds unique ways to invite you to befriend these crawling creatures that are responsible for pollination, decomposition and biodiversity.

“They do so much for us,” Angus says, “and they really don’t deserve the torment that we put them through.” –MG

10 Things the Wisconsin Bug Guy Wants You to Know

For the past 10 years, entomologist P.J. Liesch — better known as Wisconsin Bug Guy — has served as director of the UW–Madison Department of Entomology’s Insect Diagnostic Lab. He’s the guy researchers, business owners, landscapers and citizens call or email when they find a bug they can’t identify, and he fields 2,500 such requests each year. Ninety-five percent of them come from Wisconsinites, but Liesch has also identified insects in all 50 U.S. states and close to 50 other countries. In his lab, where coffee mugs and glass beakers hang on the same rack, the walls are papered with newspaper clippings he’s quoted in (like The New York Times’ piece on murder hornets), hand-drawn thank-you pictures from area children and insect-inspired posters that say things like “Keep Calm and Carrion.” Outnumbering this ephemera are the insect specimens themselves — most dead, but some living. Right now there’s a tiny, live scorpion keeping Liesch company beneath a rock in a little plastic case on his shelf.

“This year, one thing that has stood out to me is I’ve had not one, but four cases of live scorpions found in the state ... including two here in Madison,” he says, adding that scorpions are not native to Wisconsin, which means they got here some other way. “In all my other years in the lab, I’ve had maybe two or three reports, and they were essentially dead on arrival.” Serving as a sort of detective for cases like this — he was able to identify this particular scorpion as a suitcase hitchhiker from a Wisconsin resident’s recent California trip — keeps Liesch’s job exciting. But what he really loves is serving as an ambassador of sorts for the bugs themselves — helping them communicate to the rest of us why we need each other, and how best we can live together.

“The big thing I really do is provide context,” says Liesch, who credits growing up next to both a rural Wisconsin dairy farm and an exotic animal preserve for his lifelong love of biodiversity. “Every insect has a different story to tell, and if you don’t understand what the insect is and what its story is, you don’t really know what it’s doing in the world around you.”

Here are just 10 of those stories.

1. There are about 20,000 insect species in Wisconsin.

And that number doesn’t even include critters like spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, crustaceans, centipedes or millipedes, which along with insects belong to the arthropod family.

2. Most insects aren’t “true bugs.”

If Liesch is talking to the general public, then yes, “bugs” includes all of these crawly critters. But if he’s talking to a fellow entomologist and says “bugs,” they’ll think he means the order Hemiptera, or “true bugs” — a group that contains things like stink bugs and box elder bugs.

3. Only 2% of insects are actually pests, and even fewer are harmful to humans.

While we can all name enemies — mosquitoes are at the top of our list, and even those provide a food source for bats, birds and other animals — the overwhelming majority of insects are beneficial. Some are harmless, many are pollinators, and most serve as a food source and/or prey on other insects, including the 2% or so that are harmful. “If someone finds a spider in their house and they’re worried, the two top questions I get are, ‘Is it a brown recluse?’ and ‘Is it a black widow spider?’ ” Liesch says. “And maybe it’s a crummy photo, but at least I can tell them it’s not either of those, and then at that point they may not really care what it is, they just wanted to sleep better that night.”

4. One out of four animal species is a beetle.

“Most folks don’t realize the mind-boggling diversity of beetles that are out there,” says Liesch. “They’re the single most diverse group of animals on the planet.” Based on sheer numbers alone, some beetles are bound to be pests, like weevils or the emerald ash borer, an invasive, wood-boring beetle that’s decimated ash tree populations throughout Wisconsin. But the vast majority of beetles are great decomposers and predators of other insects. You may not even realize that fireflies are beetles — as are ladybugs, which help farmers and gardeners by gobbling up aphids, mites, mealybugs and other pests.

5. 35% of the world’s food crops rely on insect pollination.

In addition to pollinating 75% of all flowering plants and 35% of the world’s food supply — everything from coffee to chocolate — insects are also nature’s recyclers. They break down fallen plant material, leaves, logs and rotting stumps — an act scientists refer to as “ecosystem services ... in a nutshell, something that Mother Nature does for us so that we don’t have to,” says Liesch. “If all the insect pollinators disappeared overnight, humans would have to either invent some technology or we would have to do the manual, back-breaking labor of taking a paintbrush and moving pollen from one flower to the next.”

6. Insects are threatened worldwide.

“There’s a building body of evidence that there are insect declines going on,” Liesch says. One of the most prominent headlines in recent years involved a study out of Germany that showed a more than 75% decline in flying insects from 1989 to 2016. Liesch says the scientific consensus is that there’s not one single cause. “It’s kind of death by a thousand paper cuts,” says Liesch, citing climate change, anthropogenic changes to landscape, light pollution, drought and extreme weather events. “I think we’re going to hear more and more about it in the next 10 to 20 years as more research is done.” On a hopeful note: Insects are hundreds of millions of years old, predating the dinosaurs. “So, very, very successful, evolutionarily speaking,” says Liesch.

7. You don’t need pesticides.

“My main role here in the lab is to identify insects and related creatures for people, and if it happens to be a pest species, discuss what they can do about it,” Liesch says. “In a lot of cases, it’s really getting the point across that you don’t need to spray an insecticide to control that pest. In some situations, that can actually make it worse, or you’re just wasting money.” Pesticides contribute to environmental degradation, so Liesch is happy to talk about better solutions for rejecting unwanted guests in your house.

8. Moths fly under the radar.

The pollinator world has its share of unsung heroes, and the moth is one of the most prominent. Primarily nocturnal, moths far outnumber (about 90/10) butterflies, their colorful relatives in the order Lepidoptera. But moths’ pollinating prowess goes mostly unrecognized because they often take the night shift. “So those are really kind of an unsung hero in my book that I think folks need to recognize more,” says Liesch.

9. Wisconsin’s lush landscape provides the perfect dragonfly habitat.

Because juvenile dragonflies and damselflies are aquatic, our abundant lakes, streams, marshes and wetlands help support over 160 species of Odonata. The Wisconsin Dragonfly Society is a citizen group that goes out in the field and tracks dragonflies, including the federally endangered Hine’s emerald. The WDS sends its data to the Wisconsin Odonata Survey, which now has more than 30,000 records.

10. The Wisconsin Insect Research Collection is home to more than 3 million curated specimens.

Liesch’s Insect Diagnostic Lab is part of the UW entomology department, which takes up about three floors of the north wing of the Russell Labs building. It’s helmed by department chair Russell Groves and currently has 11 faculty members. On the floor above Liesch’s lab, Daniel Young is director of the Wisconsin Insect Research Collection, or WIRC. It’s filled with floor-to-ceiling cabinets containing stacks of drawers, each of which might have several hundred specimens for an estimated total of more than 3 million. These include insects of every kind, collected, pinned and meticulously labeled in tiny handwriting or microscopic fonts. –MG and AK

Join the Bumble Bee Brigade

While honeybees tend to draw the most attention, bumble bees are critical pollinators, too — and they’re in trouble. But in Judy Cardin’s yard, any of Wisconsin’s 20 species of native bumble bees — including the elusive and endangered rusty patched bumble bee — can find a haven. She’s happy to offer people tours of her Madison yard for gardening inspiration or simply a chance to spot the bumble bees.

“They can come to my yard anytime,” Cardin says of the pollinator’s paradise she created with her husband, Robert Plamann, complete with native wildflowers like wild geranium, Culver’s root, wild bergamot, anise hyssop and aster. “Honestly, it’s one of the best places in Wisconsin to see bees.”

The population of the rusty patched bumble bee, which was placed on the endangered species list in 2017, has dropped by 87% in the last 20 years. They’ve vanished from most of their typical habitat, but southern Wisconsin has become a kind of stronghold for the struggling species. Cardin says her other favorite areas for spotting bumble bees include the UW Arboretum, Holy Wisdom Monastery in Middleton, Badger Prairie in Verona and The Dawley Conservancy in Fitchburg. “The best thing is to go someplace where there is a diverse planting of flowers,” says Cardin.

Beyond her pollinator-approved yard, Cardin serves as an educator for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Bumble Bee Brigade program. Citizens can submit photos of bees to the Bumble Bee Brigade website. Cardin has created ID cards to help intrepid bumble bee watchers recognize different species, and she is also one of the program’s “verifiers,” meaning she checks incoming images to confirm the species designation.

“All of that data — what bees are seen, where in the state and when, and what flowers they’re using — gets used by the DNR to help manage bumble bee populations,” says Cardin. Spring tip: Cardin curated an assortment of native wildflowers for the Friends of the Arboretum Native Plant Sale called “Mixed Garden Kit — Endangered Rusty Patched Bumble Bee Garden.” Curbside pickup for the online sale is available at the UW Arboretum in May. –AK

Lightning Bugs, Fireflies — Whatever You Call Them

Twenty-five identified species of fireflies live in Wisconsin, according to UW WIRC Director Daniel Young. The number is up from 23 in 2020, when he himself collected one in Hemlock Draw in the Baraboo Hills that hadn’t been identified before. The next time you see fireflies swooping and blinking their beautiful Morse code-like messages, know that you’re probably viewing an all-male chorus. Only male fireflies actually fly — female fireflies rarely fly and most don’t even have wings. All firefly larvae light up, or bioluminesce, in order to ward off predators. Later, as adults, they’ll light up to attract mates. If a whole group gets together in, say, a tree, they may sync up their lighting patterns. You can support firefly habitats by turning off lights, leaving leaf litter and adding native plants and grasses to maintain the damp soil and moisture-rich vegetation they need to lay their eggs. -MG

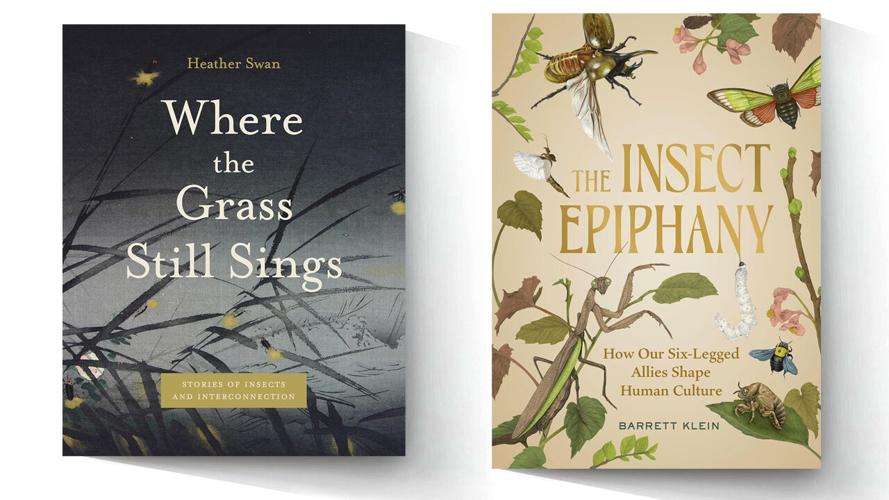

Two Books For Bug Lovers

At last year’s Wisconsin Book Festival, two Wisconsin insect devotees — UW-Madison English department lecturer Heather Swan and University of Wisconsin–La Crosse entomology professor Barrett Klein — gave back-to-back presentations on their 2024 books, both of which celebrate the intersection of art and science through insects and biodiversity. Swan is also a poet, and her lyrical prose is on display in her book “Where the Grass Still Sings: Stories of Insects and Interconnection.” Filled with bug-inspired art and artists (including a chapter on Jennifer Angus, who is also referenced in Klein’s book), personal stories of growing up among the flying critters her mother insisted on naming, and facts both illuminating and dire, the book is a must-read for anyone who wants to meditate on our relationship with the insect world.

Klein’s book, “The Insect Epiphany: How Our Six-Legged Allies Shape Human Culture,” is equally artful, celebrating insect-inspired works from numerous artists including his own mother, Karen Anne Klein. While Klein’s book covers the gamut of weird and wonderful entomological facts, it also revels in the beauty — he even assists bugs in making art of their own. In addition to doing things like giving a bee colony a bicycle helmet on which to build unique honeycomb structures, Klein gave a copy of his new book to a fellow entomologist’s termite colony so the termites could eat artful patterns into the pages (pictured below), which he then displayed at the Book Fest event. Both authors ask the reader to imagine a world without bugs, and how brutal that would truly be. –MG

Nature’s Sequins

Jennifer Angus says that in the Victorian era, clothing designers would cut jewel beetle wings, known as elytra, into shimmering disc shapes. Many other cultures have also used insect embroidery, including in Thailand and Papua New Guinea.

Pretty in Pink

You might be able to thank bugs for your favorite shade of lipstick. “I always say to people, if you’re wearing lipstick, you probably have some bug juice on your lips,” says Angus. Cochineal, the same insect colorant that Angus has used to make paint, is a natural dye found in some cosmetics.

The Mighty Fruit Fly

In addition to being the first living organisms from Earth to enter space (and the first to reproduce in space), the fruit fly (or Drosophila) has been responsible for loads of critical research. Fruit flies are cheap to source, easy to maintain and share 75% of the genes that cause diseases in humans. Nearly a dozen pharmacy, bacteriology, biology, genetics, oncology and other researchers are currently studying fruit flies at UW–Madison.

Eat Your Bugs

If you really want to expand your horizons and think about bugs on a whole other level, make a note to watch for the UW Slow Food and Undergraduate Entomology Society’s annual Swarm to Table event next year. Billed as a “celebration of insects in food, art and human culture,” past activities have included an arthropod-inspired open mic, insect-positive art gallery and, as the name suggests, a gourmet insect-tasting menu.

Picnic, Learn and Inspect at This Fest

Wisconsin Insect Fest is a celebration put on by the UW Entomology Department in late summer. (A notable exception was 2024’s Cicadapalooza, which took the place of Insect Fest to put full focus on the rare 17-year cycle.) Look for the event this summer.

Can the Woolly Bear Predict Winter?

Woolly bears are the subject of much folklore, including the belief that the wider the black bands on these caterpillars’ bodies, the longer and more severe the winter will be. While modern science has debunked these theories (variations in coloring are determined by age, species and feeding habits), the woolly bear, unique to North America, is still important as both a food source for birds and a muncher that helps break down plant materials. In the spring, they become beautiful Isabella tiger moths.

The Dragonfly Muse

Leonardo da Vinci was so captivated by the dragonfly’s unique wing beat patterns — it’s one of the only insects that can fly backwards and upside down — he used it as a model for his inventive flying machines.

Maggie Ginsberg is a contributing writer to Madison Magazine. Anna Kottakis is digital editor at Madison Magazine.

COPYRIGHT 2025 BY MADISON MAGAZINE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THIS MATERIAL MAY NOT BE PUBLISHED, BROADCAST, REWRITTEN OR REDISTRIBUTED.